Cruising the Chicago River, Illinois Waterway, Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers to the Kentucky Lakes and Tenn-Tom Waterway

It was a warm and rainy September Monday when we left DuSable Harbor for the Chicago Lock to begin the Inland Rivers segment of our Loop cruise. Strong north winds and heavy rain made the short distance to the lock an uncomfortable trip, and we waited alongside Navy Pier in confused seas. We were happy to be boating the Inland Rivers and cruising our trawler from Chicago IL to Mobile AL. The trip included cruising the Chicago River, Illinois Waterway, Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers to the Kentucky Lakes and Tenn-Tom Waterway

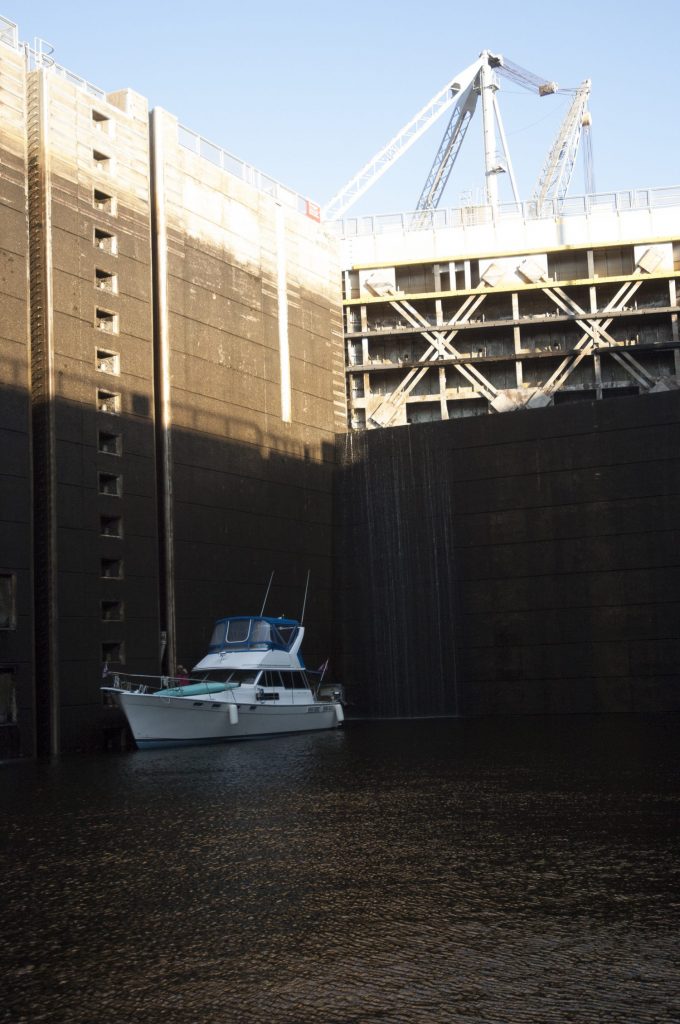

The only boat at the Chicago Lock, we were relieved to enter calmer waters once we were inside the lock. As we made our way down the Chicago River early morning pedestrians crossing the bridges above us battled with their umbrellas in the wind. It was a vivid reminder that summer was behind us and we needed to set out for warmer environs.

That morning, we had gone over the numbers one more time: On this leg of our Loop cruise, we would head south for 330 miles on the Illinois Waterway, then put in almost 220 miles on the Mississippi. From there, the route would lead east on the Ohio River for a short 60 miles before reaching the Tennessee River and Kentucky Lakes. The leg to the Tennessee Tombigbee Waterway would be another 215 miles, and then we would run 450 miles beyond to Mobile. All told, that meant about 1,200 miles on the rivers.

From the Loopers who had gone before us, we had heard mixed reviews of the rivers, so we were not sure what to expect. Nonetheless, we remained curious: Would we face miles of barren shoreline, enormous locks and fast flowing waters? We would soon find out.

A slow, low mileage day leaving Chicago

We knew there were twenty-six locks between Chicago and Mobile, but we didn’t know if we’d be able to pass right through each one or might have to wait periodically, since commercial vessels trump pleasure craft These variables made planning an itinerary iffy. Each day, we documented our progress by using the mileage marks on the river charts and in the cruising guides, sharpening our subtraction skills as we counted down the miles.

We didn’t get far that first day. To our surprise, the Amtrak bridge near Chinatown on the south west side of Chicago— was closed for maintenance until two p.m. Usually, this information is broadcast in advance on the VHF by the Coast Guard, but we didn’t hear a thing. With no other alternative we tied to a bulkhead at a small city park featuring an interesting, pagoda-like building.

Not long afterward we were joined by Free Spirit, a Jefferson 43, and by Algernon, a thirty-four-foot catamaran with its mast lashed on deck. Since we were all at various stages of the Loop cruise, we passed the day talking about our adventures. Later that afternoon the bridge finally opened, and after passing through we were grateful to find space at the old Crowley’s Boat Yard just beyond, knowing there was nowhere else to go before dark. Over a potluck dinner, we all agreed that traveling only five miles in our first twelve hours out was not an auspicious beginning.

The next day we sounded our horn and blew up balloons to celebrate Free Spirit’s completion of the Loop in south Chicago. The crew passed the marina where they had begun their journey a few years earlier.

Plowing on downriver, we were intrigued to see the industrial underside of the city. We passed huge stone quarries, where barges were being loaded high with gravel and rocks. Elsewhere, refineries and power plants lined the shore. Everything we’d heard and read about the Illinois River was true: It’s a hard-working industrial thoroughfare where marinas are few and far between.

During those first days on the Illinois, we had plenty of practice in passing huge towboats and barges full of grain and chemicals. And we grew adept at traversing the waterway’s locks. The cappuccino-colored river stood in stark contrast to the clear, blue-green waters of Lake Michigan, but as we traveled south, the industrial shoreline soon gave way to a rural landscape of trees and grasses. As we neared Starved Rock State Park, massive limestone ledges created a dramatic backdrop, with snowy egrets and a large flock of white pelicans soaring above.

The river is like a funnel, leading all boats south, so as we progressed, we met more Loopers. We found a whole gang of them at Ottawa, a nice Looper-friendly town with free docks where locals stopped by to say hello and to see if anyone needed their help. Captain Mo, a veteran Looper himself, and Larry, a retired grocer, chauffeured us around to do laundry and shopping.

TIP Our firsthand experience using binoculars on a boat: Binoculars are vulnerable on a boat. An unexpected roll from a passing boat wake can send binocs onto a hard deck surface or worse, bouncing off the boat. To protect binoculars, stow them near the helm so they’re readily available but tucked in a safe cubby that prevents them from being damaged.

At night we gathered for social hour at a picnic table to discuss our travels. Most of us were on the AGLCA/Google email list and were receiving daily postings from those underway. We appreciated the updates from the crews ahead of us, as they noted favored marinas, anchorages, restaurants and the price of diesel fuel.

At the free dock in Hennepin, several of us took advantage of a diesel truck that came and filled our tanks at a bargain price. In Peoria we stayed at the Illinois Valley Yacht Club and Marina, where we had a nice visit with family members.

Learning to be river rats

We began to pick up the lingo, expressions unique to river cruising. For example, “The wickets are down” meant that we didn’t have to go through the lock ahead because the water was high from recent rains. Instead, boats like our High Life could pass alongside the lock.

Compared to those in the Erie Canal and the Trent-Severn Waterway, the locks in this area were much larger and designed for commercial traffic. They also had a floating bollard system that made passage easy for cruisers. We rigged both sides of the boat with a couple of large, round fenders and with bow, amidships (spring) and stern lines.

Having lines and fenders to port and starboard gave us the flexibility to go to either side of the lock wall at the last minute. This happened if the boats ahead of us changed their docking plans. With this setup the helmsman would simply drive into the lock and, when the boat stopped opposite the bollard, the deckhand would Loop the amidships line around it.

We enjoyed our stay at the Tall Timbers Marina in Havana, where the staff passed out coffee and homemade cinnamon roll-ups in the morning. The brick streets downtown led us to a local hardware store and at the riverfront park we chatted with passengers on the Delta Queen, who were curious to meet real “boat people” cruising aboard their own vessels.

Our last stop on the Illinois River, at Hardin, wasn’t a marina at all but two enormous yellow barges lashed together in front of Mel’s Riverdock Restaurant, highly recommended in the Loopers’ email chatter for its two-inch-thick pork chops. A gang was waiting there to catch our lines. “You have at least ten feet of depth,” someone called out. We heard, “You’re bucking about a knot of current” from another. The sense of camaraderie was building among our roving community.

The Mighty Mississippi

At Alton, IL we entered the Mississippi River, more olive drab in color, and faced a 218-mile run to the Ohio. This stretch is known for its lack of fuel stops, marinas, and anchorages—and for its powerful two-knot current. The passage lived up to its reputation on all counts.

We made our way south, with Illinois on the east and Missouri on the west. Just beyond Alton a large sign featuring a big arrow directs all river traffic to port and into the Chain of Rocks Canal. Despite its name, this is a better route than the river’s main channel, which is truly rock laden and characterized by strong currents and rapids. We referred often to river charts we had borrowed from our friends aboard Falconer, a six-foot draft sailboat. They had made the trip earlier and had written, “NO! NO! NO!” and large Xs over the main river channel, alerting us to its hazards. (We later heard that one of the Loopers had missed the turn into the canal and had suffered expensive hull and prop damage.)

There were also plenty of notations about water depth and places where our friends had anchored. Most Loopers sell their reference libraries after completing the trip, so there is a ready supply of used charts, they’re not only cheaper but are also often filled with invaluable firsthand information. It was hard to visualize Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn lazily floating down this busy waterway on a raft because there was constant barge and tow traffic, including many “six by sixes” lashed together and powered by a three-story-high pushboat.

We tipped our hat to the famous arch as we passed downtown St. Louis and continued south of the city to the infamous Hoppie’s Marina, a string of barges that have been there since the 1930s. Hoppie’s wife, Fern Hopkins, is considered an expert on river conditions because she talks to the tow captains on a regular basis. She caught our lines and suggested that we might enjoy seeing her little town of Kimmswick. As we were walking up a steep road, a man in a pickup slowed to ask, “You are looking for Kimmswick?” whereupon he pointed us down the hill and in the right direction. Once there, we toured the small shops and enjoyed lunch at the Blue Owl Restaurant and Bakery, obviously an area favorite.

Later that afternoon, after more cruising boats arrived, we sat on the dock under a sign that read, “Wine a bit; you’ll feel better” and listened to Fern’s advice. We made notes on our chart books about the best and sometimes only places to tie up and anchor on the Mississippi; she also advised us of the latest reports from barge and boat captains. For example, one cutoff in the riverbank looked like a promising anchorage on the chart, but Fern reported that it had recently silted in.

We asked how many Loopers she usually saw in the fall and were surprised to hear her say that during the previous year she had counted three hundred, including “the regulars”—snowbirds from Minneapolis. A strong tornado-type weather system was predicted for the Ohio River Valley the next day, so Fern suggested that we stop at the Kaskaskia River Lock, about forty miles away, because it is protected and off the river.

We reached it early and found an almost surreal setting. A massive pair of three-story-high cement casings supported a floating approach wall, allowing it to rise and fall according to the height of the river water. By day’s end a collection of Loopers had arrived at the lock.

As we sipped wine, we watched the live satellite-weather display on the chart-plotter screen aboard Sea and saw the storm cells move across the area. It wasn’t long before all of us scurried back to our own boats as the wind and rain arrived, and we heard a tornado siren in the distance.

After a stormy night at the lock, the next day’s local news reported that a tornado had, in fact, touched down nearby and destroyed homes, created extensive power outages and knocked down trees for miles. We stayed another day to let the river calm down after hearing other boaters say that the Mississippi was a minefield of debris.

Shortly after leaving the lock, the damage on shore was obvious, and we slowly made our way south, dodging tree stumps and branches floating in the river. In stark contrast to the dark and wild waters, we saw large clusters of beautiful Monarch butterflies as they migrated to Mexico. With the strong current, our normal eight mph cruise speed rose to ten mph. at just fifteen hundred rpm. That night, our options were to anchor in a drainage ditch or tie to the abandoned barges at Gray’s Point, where the owner had given several Loopers ahead of us permission to moor.

Our flotilla of ten vessels—Triumph, Miss Liberty, Sequel, Grand Finale, Double JJ, Janie O, Algernon, U & I, Homeport, and High Life—passed by the rusty barges, turned into the four-knot current and managed to tie up without incident. Our days on the Mississippi were stressful, and we all knew if anyone got into trouble, we’d have to rely on each other because towboat service was far away.

We were gaining confidence, though, and passing even the largest tows, which appeared to fill the entire width of the river. As we approached a tug muscling barges up the river, Gene would hail her on the VHF and say, “Captain, we’re the southbound pleasure craft coming your way. Which side do you want me to pass you on?” In a very Southern, often Cajun drawl the captain would reply, “One whistle, Cap’t.” That’s river-speak for: “I’m turning to starboard, so pass me on my port side.” Two whistles mean: “I’m turning to port, so pass me to starboard.” When we met a barge at a turn in the river, its captain would usually tell us to “take the point,” meaning that he wanted us to go inside the turn so the tow could swing wide. We were getting the hang of river lingo.

Heading upstream on the Ohio River

As we turned up the Ohio River, we faced a stiff four-knot current that dropped our speed down to four knots. The nasty brown water churned and swirled, giving us pause. The run to the Kentucky Lock was only sixty miles, but it was slow going.

With nowhere else to stop for the night, we anchored in the river itself, across from the New Olmsted Lock, which was still under construction. Our flotilla of Loopers had spread out; some rafted together behind an indentation in the shoreline, while late arrivals like us were nearer the main flow. Our situation was iffy at best, with massive tree branches and debris rushing by in the current.

Just before dark, a tree longer than our Grand Banks caught on the anchor line. For a while it was the skipper and his boat hook versus the tree, but before dark the current forced the tree free. Our only consolation was knowing that the anchor was well set, so we poured ourselves a drink, ate dinner and went to bed. We didn’t sleep soundly, as things thumped against the hull all through the night.The next morning, as soon as it was light, we couldn’t get out of there fast enough. Gene again used his deft hand with the boat hook to untangle a massive forest of branches entwined around our anchor line and we sped away.

We were surprised to see the large trawler Might as Well stopped dead in the river. They had snagged the cable of a renegade red marker in their prop and were stranded while waiting for a diver and tow. There was nothing any of us could do to help.

Boats cruising at the same speed banded together, our group running at eight to ten knots. That speed, of course determined how far we’d get in one day, but it also affected whether we would be delayed at a given lock because of commercial traffic or maintenance work. At Lock 52, the last one on the Ohio, the wickets were down so we passed through the adjacent turbulent waters of the river. It was difficult to believe that the lock and its building were totally submerged; all we could see was the top of a flagpole sticking out of the water.

As we slowly approached Paducah late in the afternoon, it was decision time: We could get off the Ohio there and head to the large Kentucky Lock, or continue the recommended route for another twenty-five miles to the Cumberland River, leading to the smaller Barkley Lock and into Barkley Lake. We decided we wanted off the Ohio, so we followed the fleet into the Kentucky River hoping that we’d get through the lock before sunset. We made it without a hitch, and everyone aboard our gang of boats was relieved to see the calm, clean green waters of the Kentucky Lakes on the Tennessee River. We all headed to Green Turtle Bay Marina.

Catching up and slowing sown

For the next four days we enjoyed a reunion with boats we had last seen in Canada and Lake Michigan, Loopers who had arrived ahead of us. We shared river-survival stories, rode bikes, walked trails, and joined in boat chores like laundry and reprovisioning.

The cruising lifestyle seemed a lot like being in college. Living in a dorm, going to class, and taking tests were oddly like living on a boat and surviving the daily challenges of operating it. And, of course, there was always an excuse for a party.

Many boats in the flotilla were being hauled for repair or replacement work. Some new models had system failures like faulty generators and depth sounders, while others had run aground and dinged their props. Even the most seasoned cruisers among us had fallen victim to underwater obstructions. Some of the damage was the result of operator error, but often it was just bad luck, as was the case with a friend who had run over a sunken hawser that wound around his props and bent the shafts.

We were in the area known as the Land between the Lakes, with Barkley Lake on one side and Kentucky Lake on the other. We made our way south to the Tennessee River via the latter and found plenty of pristine anchorages and marinas. Some of our favorites were Fort Heiman and Double Island where we had a beach party with the crews of Free Spirit, Total Return, and Marabob.

Farther south, at Zippy Branch, we watched a family of deer walk along the sandy shoreline at dusk. It was early October, and as we traveled south it seemed that the leaves were turning to their autumn colors.

Picnicing on an island across from Shiloh National Battlefield with Looper friends

The Tennessee River is steeped in history, and after passing Shiloh National Battlefield, we decided to stop and visit. At Pickwick State Park and Marina, we rented a car with Sheryl and Barry on Sequel and backtracked to the battlefield. We stopped for breakfast at Abe’s Grill and joined the locals in the house specialty: fried pork tenderloin on a biscuit with sawdust gravy. We were immersing ourselves in Southern living and loving it.

At Corinth we visited the Interpretive Center to learn the significance of the fierce fighting at the railroad crossing there, and then drove to the battlefield at Shiloh itself. The beautiful orchard and rolling hills created a spellbinding atmosphere; it was disturbing to know that in this bucolic setting twenty-three thousand Union and Confederate soldiers lost their lives.

The final countdown

Like most of the Loopers we talked to, we had marine insurance that stipulated we couldn’t be on the Gulf of Mexico until November 1, so we were using that date as a cornerstone for our schedule. Then, however, we learned that the Coffeeville Lock, the last on the Tennessee Tombigbee Waterway, was being shut down for a week of maintenance. Armed with this information we recalculated once again to avoid being stuck for a week just north of the lock.

As we continued south, Loopers were everywhere, many continuing up the Tennessee River to visit Chattanooga or go to Nashville on the Cumberland, others renting cars for the drive to Memphis. Many of us attended the Loopers’ rendezvous at Joe Wheeler State Park, on the Tennessee River. There, sixty-five boats filled the docks, and 250 people attended the four days of seminars, dinners, boat crawls, and entertainment. After the event, we stopped at the Florence Marina before making the 40-mile run to the beginning of the Tennessee Tombigbee Waterway. Comprising 12 locks and 450 miles before it flowed into Mobile Bay, this would be our final countdown on the river.

Whitten Lock, the first in the system, was the most impressive; with an eighty-five-foot drop, it’s one of the deepest single-lift locks in the States. We noticed that Tenn-Tom’s lockmasters enforce the “always wear a life vest in a lock” rule, and once we had secured High Life, they asked for the boat’s documentation papers or state registration. We kept ours on a card near the VHF, so we could respond quickly, but we had the information memorized by the time we got to Mobile. Meandering south on the Tenn-Tom, our first stop—in a protected cove at Bay Springs—was one of the prettiest. There the Aberdeen Marina fully justified its status as a favorite among Loopers. The approach is surreal and breathtaking as you wind your way along a serpentine path of markers leading into a protected cove lined with cypress trees standing in the water.

When a rainstorm kept many of us at the dock, the marina’s owner, Jeff, arranged tours of the local antebellum homes. Farther south, the marina at Columbus was another Looper-friendly place. We learned later that these same two marinas had helped one of the Loop boats when a crewmember suffered a heart attack.

Alway safety in numbers cruising the Loop

This stretch of the river was mostly desolate, with long distances between stops, so it was reassuring to know that we weren’t alone. And as we got to know other crews, we became friends and created our own security blanket when someone needed help. The crew of Katie Sue were known for their ability to create a big wake to help another boat get off a sandbar; others were deemed genius for their mechanical skills. Most of our cell phones didn’t work in this area, so we depended on each other for news and conversation.

A typical daily run on the Tenn-Tom was forty to fifty miles, but it was rarely boring, thanks to the amazing amount of tow and barge traffic. Every day we passed an endless procession of deck barges loaded with coal, gas, wood chips, benzene, and machinery. Farther south at the Tom Beville Lock and Visitors Center, we toured the 108-foot Montgomery, the last steam-powered sternwheeler to ply the inland waterways of the United States. For nearly six decades, its crews removed trees, sunken logs and debris with a derrick and grapple suspended from a boom.

In addition, the vessel’s clamshell scoop dug out and removed silt to deepen the channel. The visitors center had a scaled twenty-two-foot relief map that provided us with an interesting bird’s-eye view of the Tenn-Tom. Miles of the river ran in log straight cuts, while countless switchbacks had us retracing our steps through the almost total wilderness. Occasionally we imagined hearing the eerie banjo melody from the movie Deliverance.

We knew that as we made our way south, there would be fewer places to stop for the night, so we planned our daily runs carefully. When daylight saving time became eastern standard time, we planned an earlier departure, so we could arrive before dark. Running the river at night was unthinkable. Demopolis, at Mile 216, was the last marina before Mobile, so most Loopers stopped there to refuel and reprovision. A good-sized facility, it was a popular place where cruisers who wanted to return home for a while left their boats.

By this point, the shoreline was changing from mud to sand, and the trees were decorated with hanging moss, the first we’d noticed. Below Demopolis, the Tenn-Tom entered the Black Warrior River, a waterway that became less channelized and zigzagged as it meandered southward. We occasionally heard familiar boats in front of and behind us talking to barge captains on the VHF, but with few houses and little industry along the shoreline, this stretch seemed almost desolate.

At Old Lock number 2, which was no more than a slight indentation in the riverbank, we anchored with Tara, a thirty-seven-foot sailboat. Both crews were too lazy to put out a bow and a stern anchor, so instead we each set a bow anchor and rafted stern to stern. We suspected that our technique would create the same effect and prevent us from drifting into the main flow of the river.

The plan worked. Footloose later rafted onto us, and we all scurried below as a rainsquall hit. When we heard the rumble of a towboat’s engine, we hailed the skipper on the radio to let him know that three of us were rafted together on the eastern shore. He said he’d pass the word to other commercial traffic heading our way.

The next morning was chilly. As Footloose backed away, we saw that a ten-foot-long tangle of debris had wrapped itself around both anchor lines but had remained hidden from our view. Thankfully, a nudge of the boat hook dislodged the mess, and the current took it toward the shoreline, so we could free our anchors.

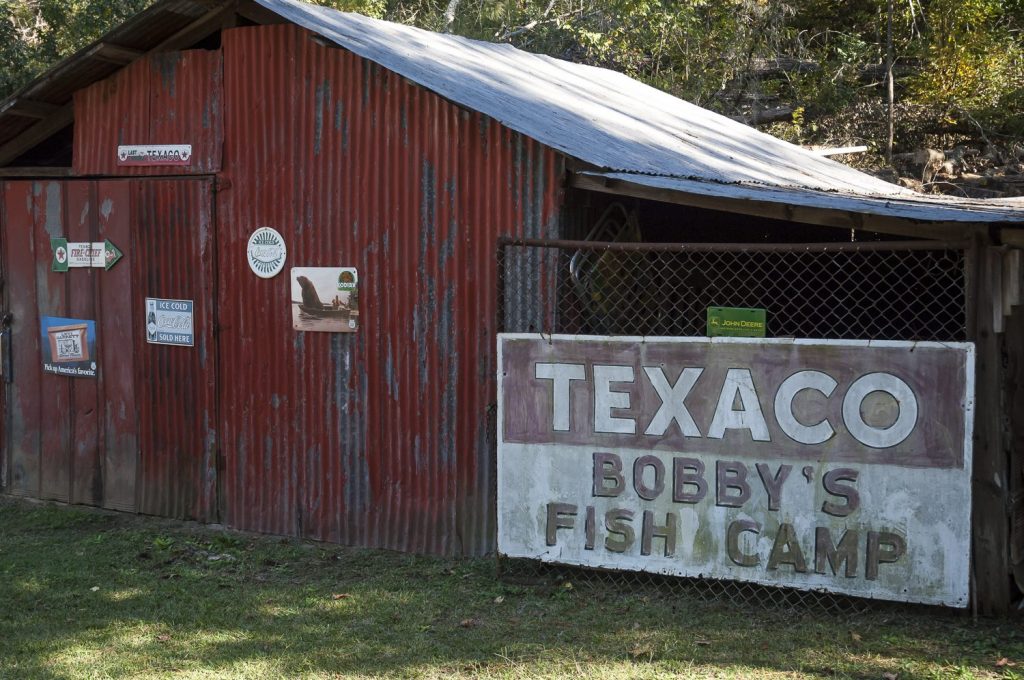

We were headed to Bobby’s Fish Camp, a legend on the river for two reasons: It’s the last fuel stop before Mobile Bay, and it serves great catfish dinners. A 125-foot mega yacht, Mimi, filled the modest floating dock, but the crew lowered their fenders, so we could raft on. By nightfall, another four boats had rafted onto Mimi, and we became part of a gang that filled the restaurant at Bobby’s. With a dusty four-foot alligator gar and deer antlers hanging on the walls, the atmosphere was one-of-a-kind, as was the dinner.

The next day we had a fifty-mile run to an anchorage, but it was eleven a.m. before all the commercial traffic got through the Coffeeville lock. We knew we didn’t have enough time to reach our goal before dark, so we returned to Bobby’s for a second night.

Our last night on the river system was idyllic, as we dropped the hook at Three Rivers Lake, a peaceful spot surrounded by cypress trees. A cold front was predicted for the next day, so we planned an early departure to reach Mobile Bay before it arrived.

At the crack of dawn, the next day, we called the lock and learned that if we got there by six-thirty a.m., we could get through. We scrambled around High Life preparing and wound our way through a morning fog to traverse the final lock on the Tenn-Tom. As we made our way through the wilderness flanking the Mobile River, we spotted our first flock of brown pelicans, and suddenly we saw the skyscrapers and ocean freighters of Mobile Bay. We watched the color of the water change from river brown to Gulf green, and we switched from the chart book we had used in the rivers to chart #11376. Armed with its overview of the bay, we followed the designated markers to the Dog River channel and then to our marina.

Once tied up, we celebrated our arrival with our friends on Pointless, who were waiting to take us to dinner in their dinghy. Later that week, as more Loopers arrived, we hosted a dock party. By then the social-hour routine was well established: Come with a drink in hand and a snack to share. Sonny Middleton, owner of Dog River Marina, sent over five pounds of steamed shrimp, and all the food was quickly consumed by the forty-plus Loopers who took part in the event.

Some boats stayed overnight and then continued to the Florida Panhandle or the southern part of the state; others had put in work orders for needed repairs. Many of us were leaving our boats in Mobile and going home for the holidays, with plans to resume cruising after the first of the year. While we Loopers were headed in different directions, we all agreed on one thing: The route’s inland rivers were an amazing cruising adventure and one we’d never forget.

If you’re considering doing the Great Loop Cruise thee’s no better resource than www.greatloop.com, the website of the America’s Great Loop Cruisers’ Assn.

- Lake Ontario to Trent Severn Waterway

- Boating the Small Craft Route of Georgian Bay to the North Channel

- Boating on Lake Huron

- Legs of the Great Loop Cruise

Gene and Katie Hamilton are veteran sail and power boaters and award winning boating writers. They are authors of Coastal Cruising Under Power and Practical Boating Skills. They are members of the Outdoor Writers Association of America.

Post Views: 6,045

|